A Dream Deferred

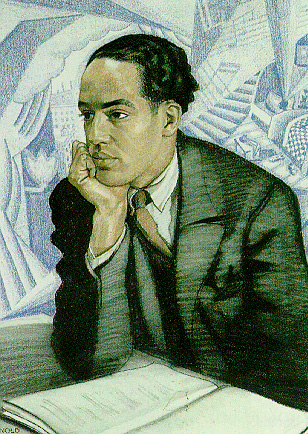

by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore–

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over–

like a syrupy sweet?Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

I absolutely love this poem; it’s one of those poems you come across every so often that makes you feel, as Emily Dickinson once put it, like the top of your head were taken off. Everything came to me in an ineffable sort of way, but as usual I’ll try to put it into words. Hughes uses simple yet striking imagery to create an intricate display of how “a dream deferred” might react. Posing the question, “What happens to a dream deferred?”, Hughes contemplates the various outcomes of this “dream deferred,” speaking about it as if it were a tangible object that might “dry up / like a raisin in the sun” or “crust over…like a syrupy sweet.” The poem’s minimalist approach—reminiscent of the Imagist poets like Ezra Pound—shoots distinct and clear visuals into the reader’s consciousness simply by using distinct and clear visuals colored with sensory qualities. These sensory descriptions alternate between the sweet and the rotten—that is, until the last line’s italicized question: “Or does it explode?” Although this poem resonates with anyone whose dreams and aspirations have been trumped by some greater power, Hughes is specifically referring to the dream of equality and freedom that African Americans’ so fervently longed for at the time. The second and longest stanza raises a series of questions concerning how the dream will react to its deferment, oscillating between “syrupy sweet” outcomes and rotting, festering, or sagging outcomes. Will the African American dream of equality sweeten through its struggles, just as a raison becomes sweeter the more it endures the suns harsh rays? Will it “sugar over / like a syrupy sweet?” Or, alternatively, “Does it stink like rotten meat?” Does it “fester like a sore / and run?” These two questions juxtapose those positive outcomes, asking whether the dream of racial equality will rot over time like dead meat, decaying in the racially polluted environment of hegemonic white society. Both results were real possibilities at the time, and to a lesser extent still are today: will African Americans ever truly break free from their brutal history of racial strife? Or will they simple exist, sagging “like a heavy load” instead of actively breaking free from racial prejudice? Obviously, it is out of their control, but their dream is still in their hands to a certain extent. The last line demonstrates this explosive break from repression and alludes to the Harlem Renaissance, when African American culture exploded with art and the conception of the “new negro,” thus bridging the gap between their parent’s more whitewashed mentalities and the individualistic and active mentality of the new generation of African Americans who found pride in their roots. Indeed, the deferred African American dream of racial equality exploded with the syrupy sweetness of artistic expression, but could it be that this explosion is a negative one? Obviously I’m speaking in retrospect here, so I know that African American rights were eventually improved and racial tensions have eased up quite a bit, but at the time Hughes wrote this poem he had no idea what the future held in store for his people. The ambiguity between whether this explosion represents a non-violent or violent shattering of racial barriers is a genuine question: how will the budding, individualistic “new negro” be accepted into society? Will they take a literal approach to fighting for freedom, or will they, as Hughes seems to subtly advocate, build themselves up until white society can no longer contain their racial individualism.

Drum

by Langston Hughes

Bear in mind

that death is a drum

beating on forever,

till the last worms come

to answer its call,

till the last stars fall,

until the last atom

is no atom at all,

until time is past

and there is no air

and space itself

is nothing, nowhere.

Death is a drum,

a signal drum,

calling life

to come!

Come!

Come!

This poem, too, took the top of my head off—I guess Langston Hughes has a way of doing that, doesn’t he. I love the metaphysical elements of the poem, particularly the notion that death preexists space, time, and the last atoms of the last worms who ate the last bit of decaying human flesh. I imagine all life smashing into a dust of nothingness as it hits the thudding drum: Death.

Death is absolute because it is the only complete truth—the only thing humans can consciously know for a fact is that they will die, colliding with “Death” the drum. And this drum is calling us, calling us like a Siren would in those ancient Greek myths I read a while back. Oddly, the beating drum cannot be time, which is “nothing, / nowhere,” even though one would assume that time is that aspect which “call[s] life / to come!” Yet time is consumed by death, leaving only that morbid drum as the omnipotent force of life. This presents a vital paradox: the journey towards death is, in and of itself, life! It may sound morbid, and to a certain extent the poem does hold cynical connotations, but philosophically speaking death is the product of life. By these means, this is a celebration of life! “Bear in mind” that all things, good and evil, stream out of that ever-conscious drum—Deaths drum pulsating with life.